Key Findings

The global impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have offered China an unprecedented opportunity to shore up its international image and influence by providing the world with medical aid and vaccines. Based on analysis of Chinese activities from 2020 to present, ChinaPower has identified six main features of Beijing’s “Covid-19 diplomacy”:

- China’s Covid-19 diplomacy is not primarily based on need or reciprocity. Political and strategic calculations—including the desire to strengthen existing relationships and forge new ones—figure prominently in Beijing’s decisions to provide medical aid or vaccines. As a result, Chinese activities have likely improved Beijing’s image and helped strengthen its relationships with countries that sought, or already enjoyed, strong relationships with China.

- China’s provision of medical aid and vaccines has frequently come with “strings attached.” This includes Chinese requests that countries show gratitude towards Beijing and support Chinese foreign policy goals. This heavy-handed and abrasive approach has led to more criticism and growing distrust of China among many countries, especially wealthy democratic countries.

- The overwhelming majority of China’s public health diplomacy has come in the form of commercial sales rather than donations. This stands in contrast to Beijing’s efforts to project the impression that most Chinese medical supplies and vaccines have been donated.

- While the United States and many other wealthy countries have donated large quantities of vaccines to COVAX (a global initiative to promote equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines), China predominantly engages countries bilaterally to augment its bilateral influence. Only a small proportion of Chinese vaccine exports have been allocated to COVAX or other multilateral mechanisms.

- Beijing has prioritized speed over quality in order to secure first-mover advantages. Concerns about the quality of Chinese medical supplies and vaccines have undercut China’s Covid-19 diplomacy.

- China’s Covid-19 diplomacy has been accompanied by aggressive Chinese information and disinformation campaigns—a topic that will be covered in-depth in the next ChinaPower feature.

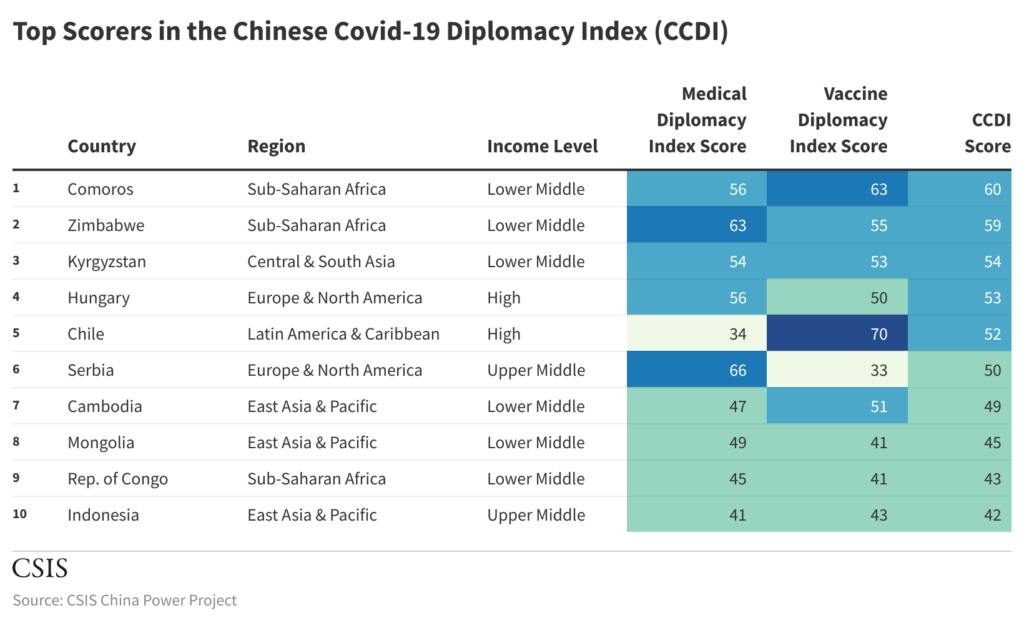

To holistically assess the scope and impact of China’s activities during the Covid-19 pandemic, ChinaPower collected thousands of data points to construct the Chinese Covid-19 Diplomacy Index (CCDI). The CCDI scores each country based on their performance within two sub-indices: the Medical Diplomacy Index and the Vaccine Diplomacy Index. Each sub-index is composed of two main pillars: Engagement and Response. The Engagement pillar assesses whether, and to what extent, China engaged a given country in terms of supplying either medical aid or vaccines. The Response pillar assesses whether, and to what extent, a recipient country’s government responded to Chinese engagement. Higher CCDI scores indicate greater Chinese influence through Covid-19 diplomacy.

The CCDI includes scores for 138 countries based on data available through mid-September 2021.1 The findings of the CCDI are preliminary since the pandemic is still ongoing and more data will become available over time, but it nevertheless provides unique insights into China’s Covid-19 diplomacy. At present, the CCDI shows a clear pattern: China’s activities have had the greatest impact in middle income countries along China’s periphery, as well as in Sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe.

The world’s largest economies (those in the G20) tend to score low in the CCDI, with the wealthiest countries such as the United States and most Western European countries earning particularly low scores. Only two high-income countries—Chile and Hungary—rank among the top ten within the CCDI. Conversely, countries with strong existing relationships with China tend to score higher. As one indicator of this, countries that have signaled their endorsement of China’s “Health Silk Road” (HSR) concept scored much higher. These trends indicate that China’s Covid-19 diplomacy was most significant in countries where China already had strong diplomatic relations and sizable influence before the start of the pandemic.

Charting China’s Covid-19 Diplomacy

In addition to the topline findings of the CCDI, our survey of Chinese activities generated several important initial findings about China’s approach to medical diplomacy and vaccine diplomacy. These findings are discussed in detail in the sections that follow, but a summary of key insights is listed below.

Medical Diplomacy

- In 2020, about 43 percent of global imports of personal protective equipment (PPE) came from China—up from 21 percent in 2019.

- Over 99 percent of PPE imports from China came in the form of sales rather than donations.

- In at least 86 countries, government officials of varying seniority participated in handover ceremonies to show gratitude for deliveries of Chinese medical supplies.

- China provided pandemic-related medical assistance to at least 63 countries, either by sending in-person medical teams or providing virtual training sessions to local experts.

- The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) delivered medical aid (including supplies and medical teams) to at least 52 countries.

- China hosted high-level special meetings on COVID-19 and issued joint statements related to medical aid and cooperation within eight different regional multilateral settings.

Vaccine Diplomacy

- As of September 7, 2021, China has finalized agreements to export 1.1 billion doses of vaccines. About 96 percent of Chinese vaccines were sold rather than donated, and 84 percent of Chinese vaccines were provided bilaterally, rather than through multilateral groupings such as COVAX.

- Most Chinese vaccines have gone to middle-income countries, rather than low-income countries.

- In 84 countries, government officials of varying seniority participated in handover ceremonies to show gratitude for deliveries of Chinese vaccines.

- Since June 2020, 27 countries have hosted trials of Chinese vaccines.

- At least 14 countries have signed agreements with China to locally produce Chinese vaccines.

- Heads of state or government in 26 countries have publicly received jabs of Chinese vaccines.

- Health authorities in at least 10 countries have suspended the use of Chinese vaccines, recommended pairing them with non-Chinese booster shots, or pushed back on them in some other way due to safety and efficacy concerns.

China’s Medical Diplomacy

As it gained control over the spread of Covid-19 at home, China quickly sought to take advantage of the pandemic to promote its influence abroad. In May 2020, President Xi Jinping delivered a triumphalist speech at the World Health Assembly in which he declared that China had “turned the tide on the virus” and was prepared to use its resources to help other countries do the same. By the time Xi gave that speech, China was already undertaking sweeping efforts to dispatch medical supplies and teams of medical aides around the world.

To gauge the impacts of Chinese medical aid activities, we constructed the Chinese Medical Diplomacy Index. The index captures the extent of China’s engagement and recipient countries’ responsiveness by assigning scores based on eight key indicators.

Expand to learn more about the eight indicators

Engagement Indicators

- PPE Reliance: The percentage of the recipient country’s total PPE imports that came from China in 20202

- Per Capita PPE Imports: The total amount of PPE imports from China in 2020 in nominal US dollars divided by the number of people in the recipient country

- PPE Donations per Capita: The total amount of PPE donated by China in 2020 per person in the recipient country

- Medical Teams: Indicates whether China sent medical teams to the recipient country or held virtual training sessions with local medical professionals

- PLA Medical Aid: Indicates whether the Chinese military was involved in providing medical aid to the recipient country

- Multilateral Engagement: Indicates whether the country participated in a multilateral grouping prioritized for Chinese medical aid or collaboration

Response Indicators:

- Reception: Indicates whether the recipient country’s government officials attended a medical supplies handover ceremony, and is weighted based on the level of the top official in attendance

- Reciprocity: Indicates which countries donated more PPE to China in 2020 than they received from China. Scores are normalized based on the amount of the net donation and subtracted from the overall response score to reflect the fact that many countries were angered by China’s lack of reciprocity

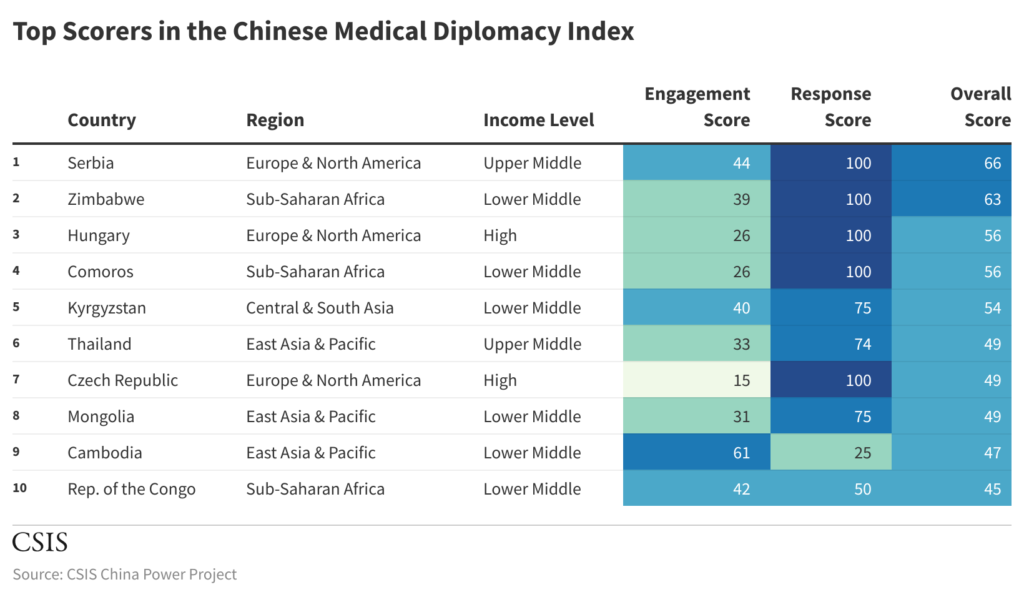

The results of the Medical Diplomacy Index indicate that the impacts of China’s activities were geographically far-reaching. Countries from Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern and Central Europe, and East Asia and the Pacific figure prominently in the top 10 within the index. Only two countries in the top ten—Hungary and the Czech Republic—are high-income countries; the other eight are middle-income countries.

Beijing may have successfully bolstered its influence in the countries boasting high scores in the index, but it is unclear how lasting the impacts will be; any boost China achieves may only be temporary. The top ten countries in the index already had substantial or strong relationships with China prior to the pandemic, indicating that China’s provision of medical aid likely did not allow Beijing to make major inroads in countries where it did not already have a significant amount of influence. In several countries—especially wealthy democratic ones—Beijing’s desire for public displays of gratitude were either ignored or provoked a backlash that diminished China’s image. As one indicator of this, neither the United States nor any western European country (other than Spain) sent government officials to welcome deliveries of Chinese medical supplies.

Assessing the Scope of China’s Medical Diplomacy

Providing countries with medical supplies has been one of the most high-profile elements of China’s Covid-19 diplomacy. Prior to the pandemic, China was already the world’s top supplier of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks, respirators, face shields, gloves, soap, and cleaning supplies. In 2019, Chinese companies exported some $25.4 billion worth of PPE, well ahead of the next-biggest global suppliers, including Germany ($17.3 billion), the United States ($13.9 billion), Japan ($6.5 billion), and France ($6.3 billion).3

Amid China’s Covid-19 outbreak in January and February 2020, Chinese companies dramatically ramped up production of various medical goods, especially PPE. According to the Chinese government’s National Development and Reform Commission, national capacity for face mask production surged fivefold during February, from 20 million units per day to 110 million per day. After China’s own outbreak was largely contained, Chinese companies began to flood global markets with exports of PPE. During 2020, China’s total PPE exports surged more than three-fold over the previous year to $78.3 billion. The other top global producers of PPE did not see similar increases in exports.

As the pandemic spread to other parts of the world, many countries became increasingly reliant on China for PPE. In 2019, China supplied 21.1 percent of global imports of PPE, but in 2020 that figure doubled to 42.9 percent.4 Wealthy countries were the largest purchasers of Chinese PPE. The United States, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom together took in half of all Chinese PPE exports in 2020. However, China saw its greatest gains in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the share of imports coming from China rose from 17 percent in 2019 to 45 percent in 2020. South Africa, for example, relied on China for 55.6 percent of its 2020 imports of PPE, compared to just 18.3 percent in 2019.

In addition to providing medical supplies, China also dispatched teams of medical professionals and advisors to assist at least 63 countries in handling the pandemic. All but four of these were developing countries (including low-, lower middle-, or upper middle-income), and 27 of them were in Sub-Saharan Africa. In some cases, China already had medical teams embedded in countries, and they were directed to assist in helping with combatting Covid-19. This was particularly common in Africa, where Chinese medical teams have been active for decades. Chinese medial teams also conducted virtual Covid-19 prevention trainings. In March 2020, for example, Chinese government officials and medical experts held a virtual information-sharing conference with officials and medical specialists from 10 Pacific Island countries.

The Chinese military played a distinct role in supporting China’s medical diplomacy. As of September 2021, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had delivered medical supplies and aid to at least 52 countries. This was typically done in the form of military-to-military aid, but the PLA also supplied medical aid for broader consumption. Many of the countries that received medical supplies and aid from the PLA were both geographically and diplomatically close to China. In April 2020, for instance, the PLA delivered medical supplies and teams of military medics to Myanmar, Pakistan, and Laos. Official Chinese media coverage noted that the aid “shows the high-level of mutual trust and friendly relations between China and these countries.”

As it engaged in medical aid diplomacy, Beijing sought to leverage existing regional multilateral mechanisms to enhance its approach. In addition to regular engagement through global organizations like the United Nations and World Health Organization (WHO), China promoted targeted cooperation on medical aid in at least nine regional and multilateral settings, including:

- A conference on Belt and Road international cooperation

- A grouping of South Asian countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka

- A vice-ministerial conference with Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka

- A special vice-ministerial meeting with Caribbean countries

- A special vice-ministerial meeting with Pacific Island countries

- The ASEAN Plus Three summit

- The G-20 Leaders’ Summit and G-20 Sherpa Meeting

- The Shanghai Cooperation Organization

A key element of China’s multilateral engagement has been promoting the development of a “Health Silk Road” (HSR), which Beijing has elevated during the pandemic as a means of promoting the broader Belt and Road Initiative. In June 2020, a group of 25 countries signed onto a joint communique that explicitly promoted the HSR concept and called for sharing experiences and information and boosting connectivity to facilitate the flow of Covid-19 prevention supplies and other public health goods. Notably, these 25 countries tended to score highly in the medical diplomacy index: six of the top ten signed onto the communique.

The Mixed Results of China’s Medical Diplomacy

While China’s medical diplomacy was sweeping in scale, it achieved only mixed results. Beijing went to painstaking efforts to cast itself as a benevolent supplier of global public health goods, but its heavy-handed approach often backfired.

In the early days of the pandemic, China’s reputation in some countries was tarnished by accusations that it hoarded medical supplies. As China drastically increased imports of critical medical goods to address its domestic Covid-19 outbreak, it soaked up supplies of those goods globally, leading to skyrocketing prices on the world market. Many countries were left scrambling to purchase medical goods from China, which often resulted in bidding wars. In Australia, these dynamics led to heated public criticism that China “drained” Australia of medical supplies when the country needed it to combat the coronavirus. In Mexico, some noted that the medical supplies they received from China were those they had previously sold to Beijing, but now had to purchase back at a higher cost.

To combat this narrative and elevate China’s image, Beijing frequently sought to extract public expressions of gratitude from officials in countries where it sent medical supplies. At the encouragement of China, many recipient countries issued public statements acknowledging Chinese medical aid contributions. Italian foreign minister Luigi di Maio, for example, praised Chinese aid on social media, and Polish Foreign Minister Jacek Czaputowicz released a statement thanking China for its aid.

Where possible, Chinese embassies abroad requested that officials in recipient countries participate in handover ceremonies to showcase Chinese generosity. Many countries obliged. Through September 2021, at least 62 countries held such ceremonies, with more than half of these attended by officials from recipient countries at the rank of minister or cabinet level, or higher.5 In Eastern and Central Europe, these public events involved top leaders from countries that had strong and growing relationships with Beijing: Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, and Czech Republic Prime Minister Andrej Babiš all welcomed and praised Chinese medical supplies in person at the airport.

While some embraced these activities in order to strengthen relations with Beijing, others such as Poland felt pressured to do so as a quid pro quo for receiving Chinese medical supplies. They viewed Beijing’s requests to show gratitude as China taking advantage of the pandemic to bully countries reliant on China. Many countries, such as India and South Korea, did not engage in such public activities and others, such as Vietnam, only provided a token gesture by sending low-level officials.

China’s heavy-handed approach was in stark contrast to the approach of other major countries. Many countries, especially in Western Europe, quietly donated medical supplies to China during the height of its outbreak. Officials in these countries expressed annoyance with Beijing’s attempts to nurture the perception that it was donating much of its medical supplies, rather than selling them. In reality, over 99 percent of China’s PPE exports were in the form of commercial sales, not donations.

Several countries also complained that China did not reciprocate the large amounts of PPE donations that they provided to China. Data from China’s General Administration of Customs shows that in 2020 China exported $212 million worth of PPE donations and imported nearly $160 million worth of donated PPE. While China was overall a net exporter of PPE donations, several countries donated significantly more to China than they received in return. South Korea was the largest net donor to China, sending $22 million in PPE to China and only receiving $5.9 million in return. The United States, the Philippines, Germany, and Japan were also major net donors, sending China more than $5 million worth of PPE than they received from China. Even several smaller, less-developed countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, and Tunisia were net donors to China.

The soft power gains that Beijing reaped from providing medical supplies were sometimes watered down by concerns about quality. Many of the products that China exported—from face masks to medical test kits—were defective. A few Chinese companies also took advantage of the pandemic to sell fake or sub-par quality goods. These sales substantially damaged China’s reputation abroad. Criticism of faulty Chinese medical goods were most prominent among developed countries. Of the 34 European countries examined, over two-thirds had commented on quality issues associated with Chinese medical goods. In contrast, only a handful of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa publicly commented on the quality of Chinese medical supplies.

These dynamics indicate that China’s approach led to notable diplomatic and soft power gains in some countries, and limited success in other countries. In many developed democratic countries, Beijing’s heavy-handedness likely worsened its image.

China’s Vaccine Diplomacy

In addition to providing medical aid, China joined several other countries in marshalling its economic and technological resources to develop Covid-19 vaccines. As mass vaccination has emerged as the linchpin of a global recovery from the pandemic, the provision of vaccines has become a major potential source of soft power and diplomatic leverage—and China has positioned itself as one of the world’s top suppliers of vaccines.

Our Chinese Vaccine Diplomacy Index provides a unique and comprehensive assessment of the scope of China’s provision of vaccines, as well as how countries responded to Chinese efforts. Index scores for each country are determined by nine indicators.

Expand to learn more about the nine indicators

Engagement Indicators

- Reliance: The percentage of the recipient country’s total vaccine supply that comes from China

- Donation Coverage: The percentage of the recipient country’s population covered by donated Chinese vaccines

- Sales Coverage: The percentage of the recipient country’s population covered by purchased Chinese vaccines

- Multilateral Engagement: Indicates whether the country was part of a region or grouping that China singled out for priority access to Chinese vaccines

Response Indicators

- Reception: Indicates whether the recipient country’s government officials attended a vaccine handover ceremony, and is weighted based on the level of the top official in attendance

- Foreign Leader Vaccination: Indicates whether a country’s president or prime minister is inoculated with a Chinese vaccine as of early September 2021

- Trials: Indicates the number of unique Chinese vaccines trialed in the country

- Local Production: Indicates whether the country has agreed to domestically produce a Chinese vaccine

- Problems: Indicates whether the country suspended use of a Chinese vaccine, stopped including Chinese vaccines in official counts of vaccinated totals, recommended non-Chinese vaccines as booster shots for those previously inoculated with Chinese vaccines, or began using a Chinese vaccine exclusively as a booster shot

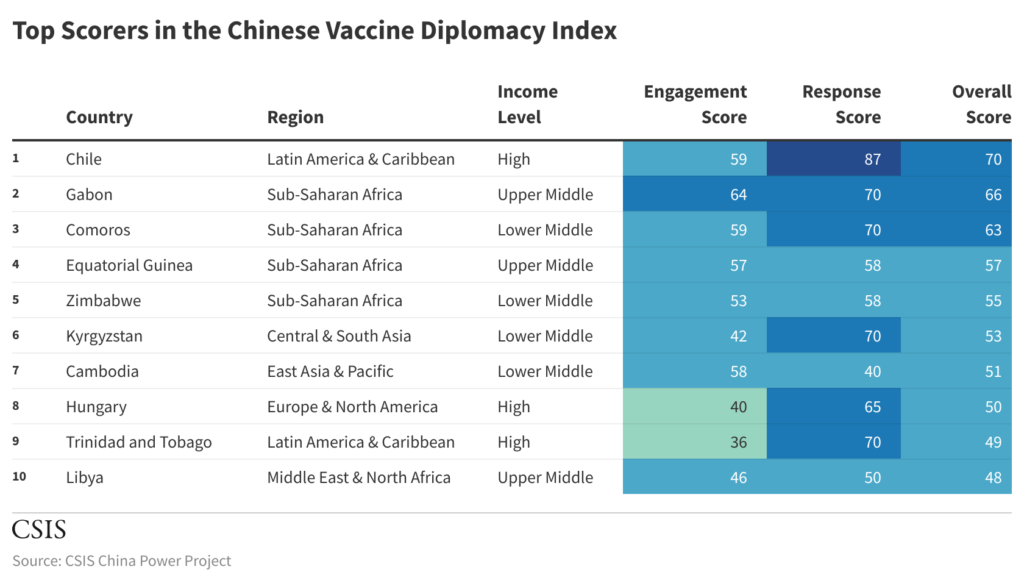

Taken together, the index reveals a far more detailed picture of China’s vaccine diplomacy to date than simply counting where China has distributed vaccines. For instance, while only seven percent of Chinese vaccines have gone to high-income countries, three high-income countries (Chile, Hungary, and Trinidad and Tobago) rank among the top ten in the index. This is largely because these countries had greater financial resources to purchase large quantities of Chinese vaccines, and because their governments were highly receptive to Chinese engagement. At the same time, four middle-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa also rank among the top 10 in the index, largely because they are highly reliant on Chinese vaccines for all—or virtually all—of their vaccine supply.

China’s vaccine diplomacy may have generated goodwill in the top-scoring countries in the index, but beyond those, it is not clear that China’s provision of vaccines has significantly strengthened Beijing’s diplomatic influence. About 96 percent of the vaccines that China has provided to the world were purchased rather than donated. Similarly, China has delivered the vast majority of its vaccines bilaterally, rather than through multilateral mechanisms like COVAX. As a result, poor countries have largely lacked the resources to purchase Chinese vaccines, and to date they have only received small donations relative to the size of their populations.

Chinese vaccines also face tough competition from vaccines developed in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. Concerns that Chinese vaccines are less safe and effective than their American and European counterparts have diminished their attractiveness. Many of the middle-income countries that have the resources to purchase vaccines have scrambled to acquire whatever they can get, meaning that their use of Chinese vaccines may reflect their desperation to inoculate their populations rather than a desire to enhance relations with Beijing. Meanwhile, few high-income countries have sought Chinese vaccines and instead have purchased American and European vaccines.

China’s Multi-Faceted Vaccine Diplomacy

Vaccine diplomacy is not simply about exporting doses of vaccines abroad. China took advantage of the multi-faceted vaccine development process to promote its vaccines abroad at multiple different junctures.

Beijing scored important diplomatic wins early in the pandemic by trialing its vaccines abroad. The first overseas trial of Chinese vaccines began in June 2020 when Clover Biopharmaceuticals initiated a small phase I trial of its SCB-2019 vaccine in Australia. The following month, stage III trials of both Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines kicked off in five countries (Bahrain, Brazil, Egypt, Jordan, and the UAE). The Chinese government widely touted overseas trials as a symbol of China’s largesse and a means of improving bilateral relations. In Pakistan, for example, Chinese state media heavily publicized a phase III trial of China’s CanSino vaccine in which 17,500 Pakistanis participated. Media coverage of the trials highlighted the close China-Pakistan relationship and quoted locals as “urgently awaiting” the vaccine amid a wave of Covid-19 cases and deaths.

Many of the countries trialing Chinese vaccines did so with the expectation of gaining priority access once the vaccines were ready for use. As of September 2021, 27 countries have participated in trials of eight different Chinese-developed vaccines. Two-thirds of these countries were middle-income countries, while the other third consisted of high-income countries. These countries that have trialed Chinese vaccines gained points in the Response pillar within the Vaccine Diplomacy Index. However, it is important to note that some additional countries, such as Cambodia, may have desired to host trials of Chinese vaccines, but were ineligible due to limited spread of the virus within their countries during trial periods.

As Chinese vaccine candidates progressed through stages of development, some countries took the additional step of signing agreements with China to jointly produce Chinese vaccines within their countries. As of September 2021, 14 countries have done so, including Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Hungary, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Serbia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. These countries saw increases in their response scores within the Vaccine Diplomacy index, but as with trialing vaccines, it is important to note that not all countries have the resources to produce vaccines domestically.

China achieved a major milestone in May 2021 when the WHO approved China’s Sinopharm vaccine for emergency use. It marked the first time that any Chinese-developed vaccine has received emergency authorization from the WHO and was widely seen as a symbol of China’s growing technological prowess, as well an indication of the world’s desperate need for vaccines. The WHO followed up in June 2021 by also approving Sinovac’s vaccine for emergency use.

With multiple vaccines approved for use, Beijing intensified its efforts to supply the world with Chinese-made vaccines. As of September 7, 2021, China has finalized agreements to provide more than 1.1 billion Chinese-developed vaccines. This includes the sale of 929.3 million doses and the donation of 45.7 million doses to individual countries, as well as the sale of 174 million doses and donation of 315,000 doses to multilateral groupings (primarily COVAX).

In contrast to its provision of medical supplies, China has provided most of its vaccines to middle-income countries. Only about 2 percent of China’s vaccines have gone to low-income countries. These countries lack the financial wherewithal to purchase large quantities of vaccines, and so far, China has only donated about 5 million doses to them. About 7 percent of Chinese vaccines have gone to a handful of high-income countries. Most wealthy countries have sought vaccines produced by US and European developers Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson, and Oxford/AstraZeneca.

In terms of geographical distribution, more than half of Chinese vaccines have gone to two regions: Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and East Asia and the Pacific (EAP). LAC has received more doses (323 million) than any other region, with Brazil (120 million), Mexico (67 million), and Chile (62 million) accounting for most of this. The EAP region has taken in 274 million doses, with the overwhelming majority going to countries in Southeast Asia. Indonesia alone purchased nearly 156 million doses making it the world’s largest recipient of Chinese vaccines by a margin of over 30 million doses. The remaining one-third of China’s vaccines are split up among three other regions, with countries like Turkey (100 million doses), Iran (51 million), Morocco (41 million), and Egypt (20 million) taking in much of this.

Several countries are highly dependent on China for vaccines. Six countries have so far procured 100 percent of their vaccine supply from China. All of them—Chad, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan—are low and lower middle-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Another 21 countries, predominantly comprising African and Asian countries, procured more than 50 percent of their vaccines from China.

Overall, of the 103 countries that have received Chinese vaccines, their total vaccine supplies have, on average, comprised 39 percent Chinese vaccines (meaning that 61 percent of their supplies have come from non-Chinese vaccines).6 Most of the countries that are highly reliant on Chinese vaccines have not received large quantities of Chinese doses. Among the six countries that received 100 percent of their vaccine supply from China, only one (Equatorial Guinea) has received enough vaccines from China to vaccinate more than 20 percent of its population. The other five have only received enough doses to cover less than 10 percent of their population.

In addition to bilateral sales and donations, China has finalized commitments of more than 174 million doses to multilateral organizations. This includes selling 174 million doses to COVAX and 50,000 doses to the South American Football Confederation (CONMEBOL) and donating 300,000 doses to UN Peacekeeping Forces.

The Limitations of China’s Vaccine Diplomacy

China’s vaccine diplomacy appears to have bolstered China’s image and diplomatic leverage in some countries. Yet the full potential of China’s vaccine diplomacy has been watered down by concerns about the efficacy of Chinese vaccines, as well as Beijing’s tendency to sell vaccines bilaterally, rather than donating them to global efforts like COVAX.

As it did with medical supplies, Beijing sought to elevate the impact of delivery of vaccines by extracting public displays of gratitude from recipient country governments. Through mid-September 2021, at least 84 countries held handover ceremonies to publicly welcome the delivery of Chinese vaccines. Nearly two-thirds these countries sent a government official of the rank of minister or cabinet level, or higher. The presidents or prime ministers of five countries (Comoros, the Czech Republic, Lesotho, Hungary, Serbia, Zimbabwe) attended handover ceremonies in person, signaling strong high-level support for Chinese vaccines. Notably, 52 of the 84 countries that held vaccine handover ceremonies also held ceremonies to welcome Chinese medical supplies.

The leaders of some countries took this a step further. According to media reports, the heads of state or government of at least 26 countries have publicly received jabs of Chinese vaccines. Four of these— Comoros President Azali Assoumani, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, and Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa) were among the heads of state or government who also attended vaccine handover ceremonies in person. Importantly, however, the decision of foreign leaders to receive jabs of Chinese vaccines signal support for Chinese vaccines, but does not necessarily mean that Chinese vaccines are the preferred option of their governments or their population. For example, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte was vaccinated with China’s Sinopharm vaccine, but many other top officials in his government did not take Chinese vaccines.

China’s vaccine diplomacy may have offered Beijing leverage to ask some recipient countries to show more support for China’s interests. There is anecdotal evidence of recipients voicing more support for China, particularly immediately before, during, or after vaccine deliveries. This includes recipients releasing statements that support Chinese core interests related to Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. There are also reports of major Chinese vaccine recipients blocking larger regional efforts to criticize Chinese activities. Hungary, for example, blocked EU statements criticizing China in April 2021, just a few weeks after the country purchased millions of doses of Chinese vaccines.

Beijing may have also been able to successfully stifle criticism of China by withholding the provision of vaccines. In the case of Ukraine, China reportedly compelled Kyiv to retract its signature from a statement criticizing China for human rights abuses in Xinjiang by threatening to withhold access to Chinese vaccine and limit bilateral trade.

At the same time, there are signs that the promise of Chinese vaccines was not sufficient for Beijing to advance its interests. Bangladesh did not shy away from publicly pushing back against Chinese warnings about its relationship with the Quad shortly before receiving vaccines from Beijing. Similarly, the promise of receiving Chinese vaccines did not convince any of the 15 nations that maintain official diplomatic relations with Taiwan to switch recognition to mainland China in 2020 or 2021. Amid a painful Covid-19 outbreak, Paraguay publicly debated the possibility of switching ties to mainland China, but authorities in Asunción did not do so, and Paraguay did not receive Chinese vaccines.

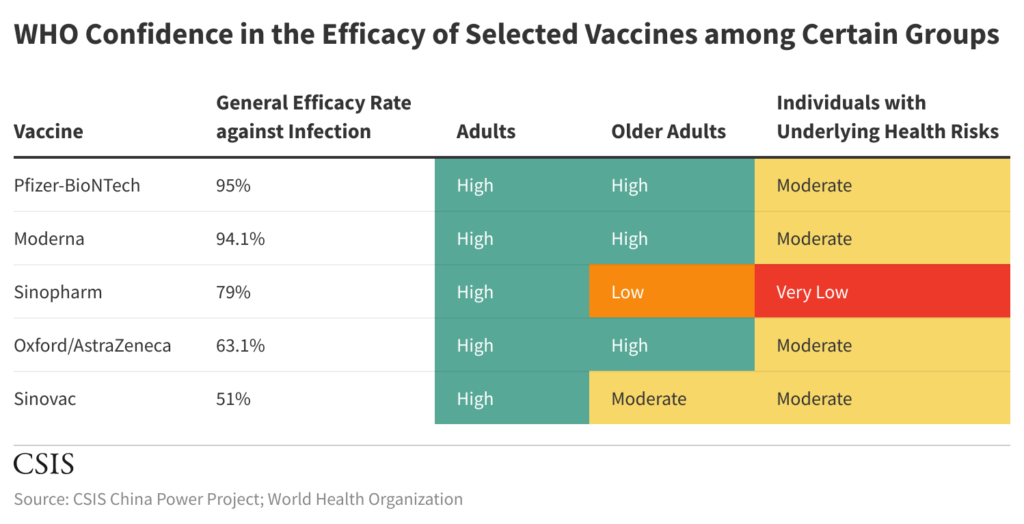

Concerns about transparency and the efficacy of Chinese vaccines have been a key limiting factor in Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy push. Many health officials around the world have expressed reservations about Chinese vaccines, especially related to their efficacy (the ability to prevent Covid-19) and safety (risk of serious or adverse effects). Sinopharm’s and Sinovac’s claimed efficacy rates of 79 percent and 51 percent respectively were based on clinical trials that mainly enrolled people from the ages of 18 and 59. In Brazil, this led health authorities to note that local trials of Chinese vaccines could not determine their effectiveness on people aged 60 and over. Similarly, the WHO’s approval of Sinopharm and Sinovac for emergency use was accompanied by caveats that the organization had lower confidence in both vaccines for the elderly as well as those with underlying health problems.

Some countries, such as Costa Rica, ultimately ended discussions to purchase Chinese vaccines out of concerns that the vaccines are not effective enough. Vaccine efficacy concerns also led several governments to reconsider their approach after initially rolling out Chinese vaccines. At least six countries—Bahrain, Cambodia, Chile, Indonesia, Thailand, and the UAE—are recommending or offering a non-Chinese booster shot to those who received Sinovac or Sinopharm vaccines. Malaysia announced that it would phase out Sinovac altogether, switching over to Pfizer/BioNTech once its supply of Sinovac doses runs out. Similarly, Brunei’s Health minister YB Dato Dr Hj Mohd Isham Hj Jaafar announced in September 2021 that AstraZeneca would become the country’s default vaccine, unless people specifically requested Sinopharm.

Singapore’s health ministry decided to omit those who received Sinovac from its official vaccine tally, citing a lack of efficacy data. In one of the most severe blows to a Chinese vaccine, Brazilian authorities announced in September 2021 that they were suspending the use of 12.1 million doses of Sinovac vaccines for at least 90 days after discovering that vials containing the shots were filled at an unauthorized production base.

Another critical factor limiting the impact of China’s vaccine diplomacy has been Beijing’s decision to donate a small proportion of its vaccines compared to major players like the United States and several European countries. Based on finalized vaccine agreements as of September 7, 2021, China’s Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines account for only about 3.8 percent of global vaccine donations. By comparison, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine developed by the United States and Germany accounts for over 44 percent of global donations. Even if China is able to fully deliver on President Xi’s commitment to donate 100 million more vaccines to developing countries before the end of 2021, Chinese donations would still make up a small portion of global donations, as well as a small proportion of Chinese vaccine exports.

China’s relatively small amount of donations is particularly stark with respect to its allocation of vaccines to COVAX, The United States has finalized commitments to donate 500 million doses to COVAX—about 50 times more than China’s existing commitments. Of the 2 billion doses Chinese President Xi Jinping has said that China will “strive” to donate globally, it is unclear what proportion will go to COVAX and how much of this has been contributed to date. It is also unclear how much of this will be in the form of sales versus donations. In terms of financial support, China has only pledged $100 million to COVAX compared to $3.5 billion from the United States. If Chinese contributions to COVAX primarily come in the form of sales, and if China does not up its financial contributions to the organization, it threatens to undermine Beijing’s efforts to be seen as a major benefactor of international efforts to combat Covid-19.

Summary

To date, China’s medical supplies and vaccine diplomacy has resulted in mixed results for Beijing in terms of its global image and influence. On the medical supplies front, countries were deeply reliant on Chinese medical supplies—especially PPE—during the pandemic. In many countries where China already had significant influence, leaders were willing to provide Beijing with the public displays of gratitude that it desired. In other countries, especially high-income countries, China’s heavy-handed approach to providing medical supplies generated frustration and complaints.

On the vaccine diplomacy front, China extracted displays of praise and support for Chinese vaccines in several countries. At the same time, China’s efforts were undercut by its decision to primarily sell rather than donate vaccines. Many of the countries most reliant on Chinese vaccines have purchased them; only a few countries have received sizable donations of vaccines. China’s vaccine diplomacy has also been limited by concerns about their efficacy, which has been exacerbated by the availability of highly effective competing vaccines.